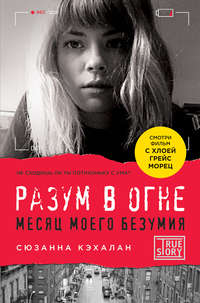

«Разум в огне. Месяц моего безумия» kitobidan iqtiboslar

“Her brain is on fire,” he repeated. They nodded, eyes wide. “Her brain is under attack by her own body.”

Because the brain works contralaterally, meaning that the right hemisphere is responsible for the left field of vision and the left hemisphere is responsible for the right field of vision, my clock drawing, which had numbers drawn on only the right side, showed that the right hemisphere—responsible for seeing the left side of that clock—was compromised, to say the least. Visual neglect, however, is not blindness. The retinas are still active and still sending information to the visual cortex; it’s just that the information is not being processed accurately in a way that enables us to “see” an image. A more accurate term for this, some doctors say, is visual indifference:35 the brain simply does not care about what’s going on in the left side of its universe.

Not only did I believe that my family members were turning into other people, which is an aspect of paranoid hallucinations, but I also insisted that my father was an imposter. That delusion has a more specific name, Capgras syndrome, which a French psychiatrist, Joseph Capgras, first described in 1923 when he encountered a woman who believed that her husband had become a “double.”12 For years, psychiatrists believed this syndrome was an outgrowth of schizophrenia or other types of mental illnesses, but more recently, doctors have also ascribed it to neurobiological causes, including brain lesions.13 One study revealed that Capgras delusions might emerge from structural and circuitry complications in the brain, such as when the parts of the brain responsible for our interpretations of what we see (“hey, that man with dark hair about 5’10”, 190 pounds looks like my dad”) don’t match up with our emotional understanding (“that’s my dad, he raised me”). It’s a little like déjà vu, when we feel a strong sense of intimacy and familiarity but it’s not connected to anything we actually have experienced before. When these mismatches occur, the brain tries to make sense of the emotional incongruity by creating an elaborate, paranoid fantasy (“that looks like my dad, but I don’t feel like he’s my dad, so he must be an imposter”) that seems to come straight out of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

“Forget you heard that, Susannah,” my dad said. “They have no idea what the hell they’re talking about.”

Reading these entries now is like peering into a stranger’s stream of consciousness. I don’t recognize the person on the other end of the screen as me. Though she urgently attempts to communicate some deep, dark part of herself in her writing, she remains incomprehensible even to myself.

The healthy brain is a symphony of 100 billion neurons, the actions of each individual brain cell harmonizing into a whole that enables thoughts, movements, memories, or even just a sneeze. But it takes only one dissonant instrument to mar the cohesion of a symphony. When neurons begin to play nonstop, out of tune, and all at once because of disease, trauma, tumor, lack of sleep, or even alcohol withdrawal, the cacophonous result can be a seizure.

I would never regain any memories of this seizure, or the ones to come. This moment, my first serious blackout, marked the line between sanity and insanity. Though I would have moments of lucidity over the coming weeks, I would never again be the same person. This was the start of the dark period of my illness, as I began an existence in purgatory between the real world and a cloudy, fictitious realm made up of hallucinations and paranoia. From this point on, I would increasingly be forced to rely on outside sources to piece together this “lost time.”

As I later learned, this seizure was merely the most dramatic and recognizable of a series of seizures I’d been experiencing for days already. Everything that had been happening to me in recent weeks was part of a larger, fiercer battle taking place at the most basic level inside my brain.

Может, верно говорил Томас Мор: "Лишь тайна и безумие приоткрывают истинное лицо души".

Когда мы вернулись в палату, он вспомнил пословицу, которая помогла мне сосредоточиться на позитивном.

– Если тебе легко, что это значит? – спросил он.

Я молча взглянула на него.

– Значит, ты летишь в пропасть, – с вымученной бодростью проговорил он, наклоняя руку и показывая склон горы. – А если тебе трудно?

Еще один непонимающий взгляд.

– Значит, поднимаешься в гору.

Some buried feeling unites me fiercely with that painting. I have since mounted it on the wall above me in the room where I write, and often I find myself staring off at it when I’m lost in thought. Maybe, even though “I” was not there to experience it for the first time, some part of me nevertheless was present during that museum visit, and maybe for that entire lost month. That idea comforts me.