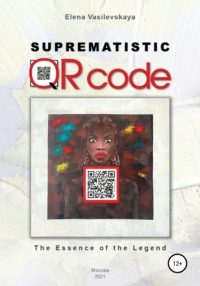

Kitobni o'qish: «Suprematistic QR code: The Essence of the Legend»

Foreword

As we explore the peculiarities of the discourse that is interesting for us, we find the proofs of our ideas. As we study Malevich’s biography and art, we fall into the world of his suprematist ideas. We find it necessary to highlight that this person has devoted his life to art completely and neither of the false rumors has stopped him from his creations. Time has made everything to be right. However, despite Malevich’s world fame his pieces of art are not fully understood. This book contains complex and objective overview of Malevich’s art movement. The following research leads its reader to the idea of suprematism global realization which happens right now, when new tendencies and technologies appear, and makes him understand that he is an integral part of this process.

The term “Square”

Here comes a thought… There are too many of them. No. They have overwhelmed everything around. They are on subways, streets, magazines, pages of the Internet, packages, business cards. Big or small, colorful but commonly black squares are everywhere, and they form a multi-component homogeneous figure.

A square is a regular quadrilateral which angles and sides are equal. However, the square considered below is only visually similar to the described figure because its sides are not equal to each other, pairwise are not parallel.

As we hear the word “square” we recall in our mind Malevich’s painting associatively. And then the figure that appears in our consciousness becomes black. It seems that drawing a black square on a white background is very simple, and this idea is primitive. However, a painting with a simple geometric figure is recognized as a masterpiece in the world. The “Black Square” (1915) is the work of Kazimir Malevich (February 23, 1878 – May 15, 1935) that is considered as his magnum opus. It is of the high value. The artist has painted many paintings. Why has only the “Black Square” occupy the minds of people?

The painting gives a mystic call to recognize its conceptual, philosophical design and becomes a reason of viewers’ indignant w-questions. It has sparked our interest to make this versatile study. Despite the fact that there are many works on K. Malevich’s art, it remains mysterious. It is still written by a person who has not been fully understood.

It is important to understand that there are too many facts about K. Malevich and they sometimes when are taken from the various sources are not identical. Malevich has deliberately provoked these differences to integrate them into his own history of art. The artist left so many mysteries! That is why a creation of the picture of Malevich’s world, which could shed light on the hidden meanings of his art, is desired.

“I guess that exploring, studying, recognizing are possible only when you can get a unit that is not connected with surroundings, that is free from any affection and any addiction. If I can do it, then I will study it, if I don’t do it, I will receive nothing but lots of pieces of excerpts and conclusions1.” – K. Malevich wrote.

The term system was Malevich’s the most favorite one. He thought that in science and art everything new was based on previous experience and following the important tendencies could make individual art valuable.

The “Black Square” is not a form that just happened. It is an evolution of Malevich’s artistic form, idea, his meaning of life.

Brief essay on history of art and politics of the beginning of 20th century

All the artistic trends that has appeared in the 20th century are usually called the avant-garde. There are conflicting styles with completely different symbols united under this title.

The “Black Square” has become the pearl of the Russian avant-garde, national and world famous symbol that has received a response from many people.

The painting is unique due to many interpretations, variations and modifications.

The role of fine art in the formation of sign systems is invaluable, therefore, its analysis becomes necessary when studying the semiotic plan in the work of a particular artist.

The increase in the number of new author’s styles and author’s techniques, as well as the return of unappreciated or misunderstood ideas, which was initially rejected by the 20th century and re-acquired relevance at the turn of the millennium, was one of the achievements of the same 20th century.

Now, at the beginning of the new century and millennium, it is important to comprehend those global changes that have destroyed the way of life that has been taking shape for centuries. Since these changes have been proceeded tremendously fast, the attitude towards time has changed, and the century brought countless different directions in art. Technical and technological capabilities have transformed the very way of creating an artistic creation using new methods: computer graphics, photography, digital means, a variety of artistic material, etc.

There was an atmosphere of transformation in the beginning of the 20th century. The proletariat and bourgeoisie were fought for the socialist reorganization of society, the social system changed, the division due to anti-religious propaganda took place. People’s minds transformed. They started to think in completely different way.

All these events had found the reflection in the artistic styles of decadence, where artists strived to show a new, perfect, changed world with a positive attitude and meaningful disappointment at the same time, with shocking and nihilistic positions towards outdated values of culture and life. The past was interpreted as something frozen, and the future as a new necessary process. This row of social catastrophes produced then some doubts on the rationality of these events. Both artists and the creative intelligentsia became the prism of that time which projected the ideas of protest, expression, individuality, and defeat. Technological innovations gave birth to belief in their own power and independence.

So-called “Revolutionaries of the avant-garde” and the Bolsheviks took concerted action only in the first post-October years. Later Socialist realism became prevalent trend and that slowed down the process of modernization of artistic culture in our country, which was taking place in full swing in Europe, for half-century.

All these events influenced trends of painting, made it changeable and unstable. After 1930 the modernist tendencies of fiction, both Malevich’s name and his “Black Square” were banned almost until the end of the 20th century.

Kazimir Malevich became world famous after a half-century delay. In Russia it happened when the Soviet ideology collapsed. In Europe it started earlier because the artist had taken away his numerous works and canvases and they found its home in the private and public collections and in the Steidelik Museum, Amsterdam.

Not only artistic works but Malevich’s philosophical and literary ones are also of the high value. In this case Malevich’s art should be studied as a concept of dormitory (Malevich called human civilization “dormitory”) which is formed by artist’s style, theoretical conclusions and the “Black Square” as a logo. To evaluate Malevich’s legacy the study must be done in a holistic and voluminous manner with the identification of the most significant moments in the life and work of the artist-thinker.

Either the study of the secrets of creativity or the facts of Malevich’s life or the artist’s thoughts, the creation of a suprematist masterpiece form a plastic formula which makes it possible to find realization of Malevich’s artistic and written prophecies depending on time and to get closer to the artist’s intention.

Black Suprematistic Square, 1915

Oil on linen, 79,5 х 79,5 cm

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow2

Becoming of the artist

Kazimir Malevich was born in a family of a sugar cook and a housewife in Kiev in 1878. Kazimir was the first child. He had four brothers (Anton, Boleslav, Bronislav, Mechislav) and four sisters (Maria, Wanda, Severina, Victoria). Malevich spent his childhood in the Ukrainian countryside. There he watched how the painted stoves and the embroidered national patterns were made. Later he recalled that this folk culture had influenced his works. When Kasimir was 15 years old his mother bought him a set of paints in Kiev. From that moment his artistic path began. In 1896 the Malevich family moved to Kursk. In 1899 Kazimir married Kazimiera Zglejc (1883–1942), the daughter of a Kursk doctor. She was a paramedic. Kazimir and Kazimiera had a son Anatoly (1901–1915) and a daughter Galina (1905–1973). Malevich worked in the Office of the Kursk-Moscow Railway as a draftsman. It should be noted that professional activity and specifically work with architectural drawings had influenced the artist’s choice of geometric shapes in painting.

Together with like-minded people Malevich organized an art circle in one of the rooms of the Administration building where they came after the government service to draw both plaster figures and people from nature. “The Exhibition of Moscow and Nonresident Artists’ Paintings” (1905, Kursk) was the first for Malevich. After some years Malevich get bored with measured provincial life. His thought to move to Moscow became obsessive.

In Kursk the first stage of K. Malevich’s creative biography began. Later the researchers classified this period as the early impressionism. The Influence of the French artists was observed in early works such as “Spring Landscape” (mid-1900s, private collection, Paris) and “Church” (circa 1905, private collection). Here Malevich made color and light effects which ranged from discrete brush strokes to neo-impressionistic pointalism with evenly covering the canvas with fine dots. Impressionism was the first step towards the term simulacrum in the postmodern philosophy of our time. Virtual reality which did not exist in reality but was created with the help of technology allowed us to comprehend possible variations of the simulation concept.

When Malevich finally arrived in Moscow in the summer of 1905, he applied for admission to the “Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture”, but did not pass the exams. He stayed in Moscow and rented a room for a nominal fee in an art commune in Lefortovo where many artists lived. But in the spring of 1906 he returned to Kursk for the government service. A year later he again moved from Kursk to Moscow with his family and tried to enter the school for the second time. The attempt was unsuccessful.

It is worth noting that since the beginning of 20th century so-called home-grown boors (students) spated3 on traditional, itinerant, naturalistic, classical art within the walls of the school where at that time the teaching was based on V. Serov’s, K. Korovin’s wonderful painting schools. They were often expelled problematically, and this process caused many scandals. These students were Vladimir Mayakovsky, Mikhail Larionov, Robert Falk, etc. This was a layer of innovators that were the so-called left painters. The same fate might have awaited Malevich.

As Malevich’s painting were neither accepted nor appreciated by the public, he fell into psychological depression. It influenced the mood of his creations at that time. But the leadership qualities of K. Malevich strengthened the desires to create, to move further, to self-express, to oppose to everything.

Either the desire for new trends or monitoring new things in art (for example, graphic drawings of the popular and often published in magazines at that time Aubrey Beardsley) left an imprint on the artist’s work.

Studying at the I. Rerberg’s School (from the fall of 1905 to 1910) was important for Malevich’s style. Rerberg’s teaching system was distinguished as flexible, comprehensive, oriented on the interests in new trends in painting. Despite the years of study here Malevich later preferred to write about himself that he was self-taught.

Since 1907 to 1910 Malevich regularly exhibited his works (XIV–XVII exhibitions of the Association). Wassily Kandinsky, Mikhail Larionov, Vladimir and David Burliuki, Natalia Goncharova, Alexander Shevchenko, Ivan Klyunkovy, etc. were among the other exhibitors.

Acquaintance with Ivan Klyunkov who took the pseudonym Klyun (1873–1943) soon grew into close communication. They became friends with Malevich who had moved with his family to Moscow and settled in Klyun’s house. Klyun used features of the canonized images and iconographic features (Orthodox) and it influenced Malevich’s style and even fell into the plots of his paintings from different periods. Elements of fresco painting, golden ink (the icon technique), ornamentation, symmetry are reflected in the work “Sketch for Fresco Painting (Portrait of I. Klyunkov)” (1907, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg). In particular, “The Improved Portrait of a Builder (Portrait of I. Klyunkov)” (1913, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) formed the basis of Malevich’s cubo-futuristic style. Pattern, rhythm, flatness are reflected in the painting “The Shroud” (1908, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

The motive of European Art Nouveau is presented in the work “Rest. Society in Top Hats” (1908, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg).

In 1909 Malevich married for the second time. His wife was the children’s writer Sofia Rafalovich (?–1925). It was important that the new father-in-law had a country house in Nemchinovka, which became a significant place for the artist until the end of his life. He tried to spend all his free time in Nemchinovka and its surroundings.

Malevich participated in a series of exhibitions which began in December 1910 when the extravagant organizer Mikhail Larionov invited the artist to the first “Jack of Diamonds” exhibition (December 1910 – January 1911). Since then he regularly took part in the shocking exhibitions of left artists who were representatives of Russian pre-revolutionary modernism (Cezanneism, Primitivism, Сubism). “Self-portrait” (1910, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), “Still Life” (1910, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) are the works of this period. At the same time the artist participated in the exhibition called “Union of Youth” (St. Petersburg, April – May 1911). The next exhibition was in Moscow. Its head was the same (Larionov), and its title is defiant – “Donkey’s Tail” (March – April 1912). Here Malevich exhibited over 20 works – “Argentine Polka” (1911, private collection, New York), “Bather” (1911, Stedelic Museum, Amsterdam), “Gardener” (1911, Stedelic Museum, Amsterdam), etc.

When at the end of his life Malevich was thinking about his art, he wrote: “I stayed on the side of the peasant art and began to draw in a primitive spirit. At first, in the first period, I imitated icon painting. The second period was purely “labor”: I drew the working peasants in harvest, threshing. Third period: I approached the “suburban genre” (carpenters, gardeners, summer cottages, bathers). The fourth period – “city signs” (floor polishers, maids, footmen, employees)”4. Malevich’s view on the origin of the religious icon was peculiarious. He considered it as the highest stage of “peasant art5.”

The main feature of Malevich’s works of this period was his desire to perceive the objective environment as the sum of individual elements where each of them received its own light and shadow modeling with a textured solution. It could be powerful sculpting of space which was made with use of colored brushstroke. There were lined up, unnaturally large, anatomically consciously increased proportions of body parts in the system of technical design of planes with a clear outline.

Subconsciously the artist used the religious icon as a model to create a planar composition as a source of rich local color which found its place monumentality on frontal figures. The objects on Malevich’s canvases seemed to be carved out from curved metal sheets. They had a steel sheen of this material. The combination of clear boundaries and pictorial content becomes the basis for the construction of recognizable real male and female figures that were presented in profile or full face with a monumental and unemotional severity of features.

The peasant series of works included “Harvesting the Rye”, “The Reaper”, “The Carpenter”, “Peasant Woman with Buckets and a Child” (all 1912, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam), “Woman with Buckets” (1912, Museum of Modern Art, New York), “Morning after a Blizzard in the Country” (1912, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York). In the painting “The Head of a Peasant Girl” (1913, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam) Malevich moved away from human features into images where cylinders, geometric designs, organized according to a kind of logic, dominated. The works reflected both high scientific, technical development and the breakthrough of that time as a projection that builds a futuristic electro-mechanized cult with the Italian roots.

“The iron-steel-concrete landscapes of the moment genre were moved by the arrows of fast time.

War, sports, dreadnoughts, throats of rearing guns, mouths of death, cars, trams, rails, airplanes, wires, running words, sounds, motors, elevators, quick changes of places, intersections of the road of heaven and earth crossed below.

Telephones, meat muscles were replaced by iron-current traction. An iron-concrete skeleton through the sighs of gushin gasoline rushed gravity.

Here was a new shell, in which our body is chained, turning into a brain of steel”6, – wrote Malevich (author’s stanza).

Combining the discoveries of French Cubists and Italian Futurists the left painters gave birth to their own ism – Cubo-futurism which became a domestic trend in the avant-garde art. The movement of Malevich’s Cubo-futurism towards “non-objective” art was made because of the influence of poets (Velimir Khlebnikov, Alexei Kruchenykh, David Burliuk, Vasily Kamensky, Mikhail Matyushin (a man of versatile talents, musician, painter, writer) and his wife Elena Guro, who created Vladimir Mayakovsky innovative association “budetlyane” (from the Russian word form byt’ – ‘to be’)). The synthesis of images, words, music led to the emergence of mutually influencing and complementary artists, poets, actors, musicians who embodied their ideas in the scandalous collection “Slap in the Face of Public Taste”.

Bepul matn qismi tugad.